Welcome. Bienvenue. Ongi ETORRI.

Andde Indaburu

How can behavioral science help address climate change while improving consumer well-being? This question drives my research.

I am Andde Indaburu, a Ph.D. candidate in Marketing at Boston University. My work explores how to promote behaviors that benefit both people and the planet drawing on insights from behavioral sciences, consumer psychology, marketing, and computational sciences. I study how individuals perceive impact, how technology shape their choices, and how well-designed behavioral interventions can shift both behavior and attitudes.

More specifically, I investigate consumers’ responses to product cues, nutrition labels, environmental messaging, and AI-generated sustainability guidance. I examine how behavioral interventions can reduce waste, overconsumption, and unhealthy behaviors, as well as how public support can be increased for policies aimed at addressing carbon inequality. I also study the role of artificial intelligence in shaping and guiding pro-environmental behavior.

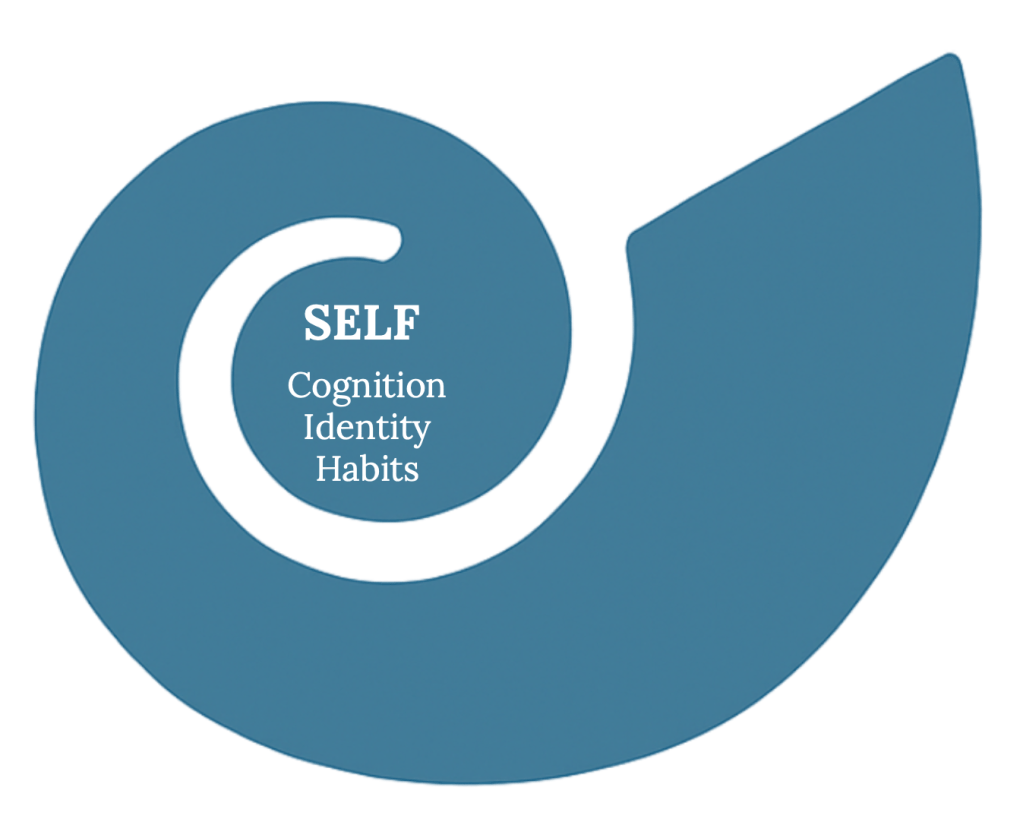

To make behavioral science more accessible, I developed the Snail Psychology framework below. It organizes behavior change into five interconnected layers, from the individual self to broader social, structural, and systemic forces, which interact dynamically to shape behavior.

The Snail Psychology

Climate change is caused by human activity across multiple levels, from individual behaviors to systemic structures. Because climate change is a systemic problem, addressing it requires systemic solutions. To effectively understand and drive behavioral change, it is necessary to look beyond the individual level and consider the several interconnected layers that shape behavior. More specifically, behavioral change should be conceptualized as a spiral that starts with the individual and progressively extends to social, structural, and systemic structures. The Snail Psychology is a framework to understand, design, and implement behavioral change across these layers.

The Snail Psychology identifies five interconnected layers (self, subjectivity, social, structures, and system) that interact continuously and dynamically to shape human behavior. The layers are easy to recall: there are five, like the letters in “snail,” and each one starts with an S. Importantly, these layers are not isolated; rather, they form a spiral shaped like a snail’s shell, beginning with the individual Self and expanding outward to the broader System. The following section defines each of these five layers (self, subjectivity, social, structure, and system) to explore how they can be applied to both understand and implement behavioral change.

Self: Cognition, identity and habits

Self refers to the internal and relatively stable aspects of a person, such as their cognition, identity, and habits.

Cognition shapes how we process information and make decisions, which is why it must be taken into account when communicating about climate change. As suggested by Daniel Kahneman, most decisions are made automatically and intuitively, with few involving deliberate, effortful thinking. People rely on mental shortcuts to simplify complex situations, often struggle to grasp abstract or large-scale concepts like CO₂ emissions, and tend to focus on the present rather than the future. Effective behavioral change strategies need to minimize cognitive effort, use intuitive cues, and present climate-relevant information in ways that are simple, relatable, and aligned with how people naturally think and decide.

Identity grounds our motivations and values, shaping how individuals see themselves and what they care about. Messages that align with one’s identity are more likely to be accepted, while those that conflict with it may trigger resistance. Research by Graham, Haidt, and Nosek (2009) shows that moral values vary across individuals: some respond more strongly to care and fairness, others to loyalty and authority. Identity signaling also plays a critical role. For instance, the Tata Nano (a low-cost car launched in India) failed commercially because it was perceived as a car for the poor, which deterred even its intended users due to the negative identity signal it carried. That is why understanding the target audience is essential, so that both the behavior and the message can be framed in ways that align with their values and perspectives.

Habits are patterns of behavior formed through repetition that become automatic over time. Because habits operate without conscious effort, they make behaviors more stable, but also harder to change. For behavioral change to be lasting, it must often become habitual. This requires repeated action, low effort, and a clear benefit. Interventions should therefore focus on making desired behaviors easy, rewarding, and consistent, so they can be integrated into daily routines with minimal friction.

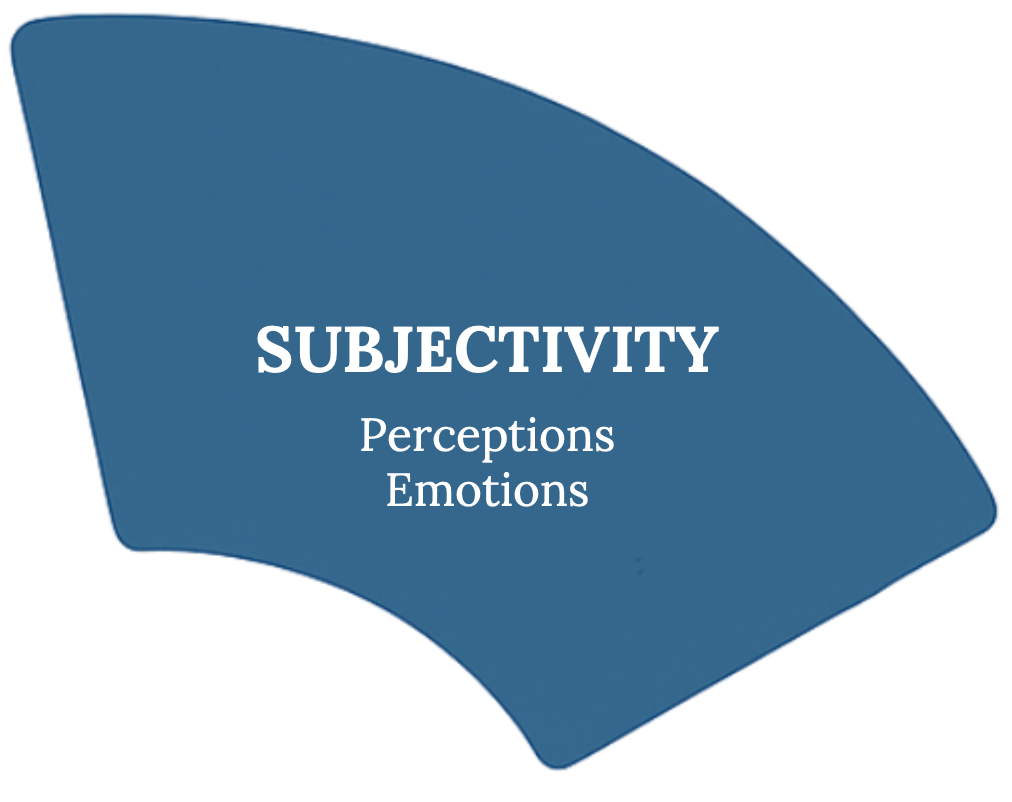

Subjectivity: Perceptions and emotions

Subjectivity refers to the external and relatively variable aspects of a person, such as their perceptions and emotions.

Perception shapes how individuals interpret information and assess their ability to act. In the context of climate change, perceived efficacy and perceived impact are key drivers of behavior: people are more likely to engage when they believe their actions make a difference. These perceptions can be influenced through interventions like personalized feedback (e.g. on energy or water use) or clear, accessible labels that communicate the environmental impact of products or behaviors.

Emotions influence both whether people act and how they act. Negative emotions such as fear, guilt, or sadness can deter harmful behaviors. Positive emotions like pride, hope, or pleasure can reinforce sustainable actions and make them more rewarding. Understanding which emotions to activate, and in which context, is essential to designing interventions that motivate lasting change.

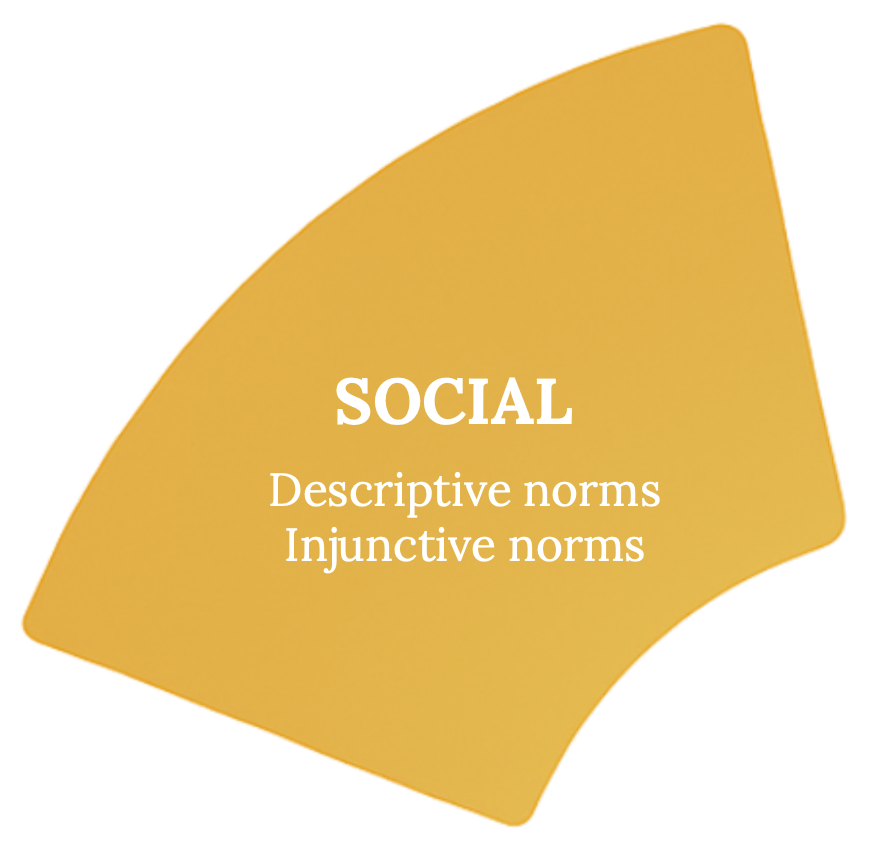

Social: Descriptive and injunctive norms

Social refers to the external and socially driven influences that come from others, such as descriptive and injunctive norms.

Descriptive norms refer to what people typically do in a given context. Individuals tend to align their behavior with what they perceive as common or socially accepted. These norms can be made more effective by using localized messaging (called provincial norms) that highlight what others in the same place are doing. Another powerful variation is dynamic norms, which focus not on what is typical now, but on what more and more people are starting to do.

Injunctive norms refer to what is perceived as acceptable or unacceptable behavior within a group. These norms guide actions by signaling approval or disapproval. Visual cues, like smiley or frowning faces, can effectively reinforce or discourage behaviors. Importantly, descriptive and injunctive norms can also be effectively combined with other interventions to reinforce messages and increase impact across different behavioral contexts.

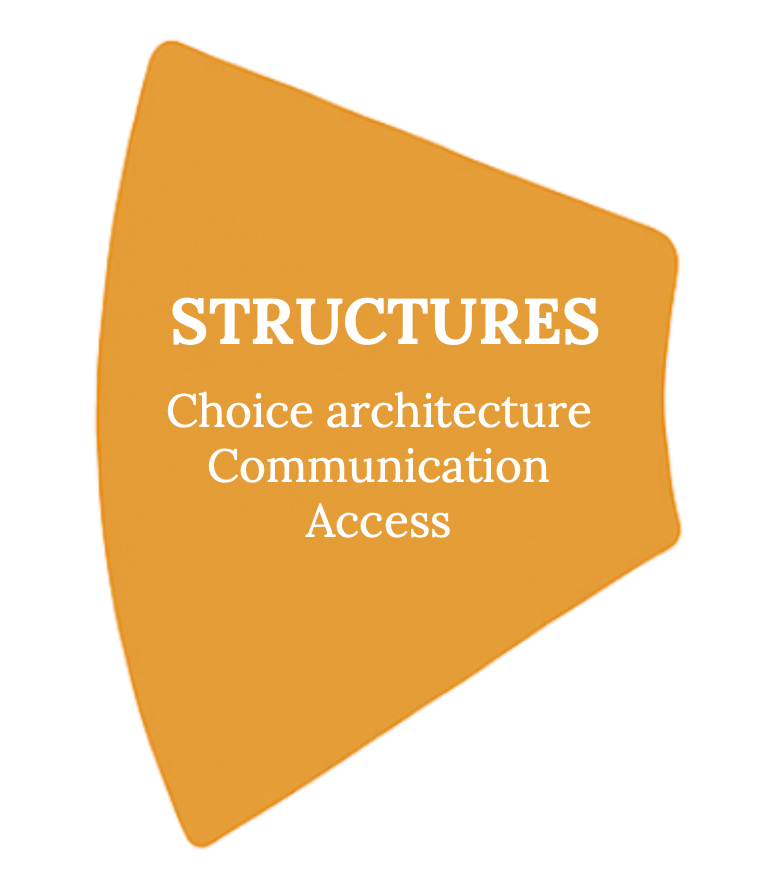

Structures: Choices, communication, and access

Structures refers to how social structures (such as companies, organizations, or institutions) influence behavior by shaping the way choices are designed, communicated, and offered.

Choice architecture refers to how choices are presented and ordered, and is a powerful levers available to organizations. Defaults are the pre-selected options that take effect if individuals do not actively make a different choice. Because many people stick with the default, they can significantly influence behavior. For example, setting renewable energy as the default in electricity contracts can increase adoption of renewable energy, and reducing default plate size in buffets can reduce food waste. The order of options also matters. As suggested in Nudge by Thaler and Sunstein, simply placing fruit and salad before desserts in a cafeteria line could encourage children to eat more apples and fewer desserts. Similarly, environmentally friendly options may be more likely to be chosen when they are presented first and when they are visible, accessible, and encountered before other alternatives.

Communication from social structures also plays a key role in shaping beliefs, values, and perceived norms. The way institutions talk about climate change, or avoid doing so, shapes public understanding and attitudes. For example, airline companies may normalize high-emission behaviors through advertising, while other organizations can help reframe sustainability as desirable and mainstream. Responsible communication strategies can support pro-environmental behavior by increasing awareness, shifting perceptions, and reinforcing social and moral expectations. Moreover, communication can leverage social norms to present sustainable behaviors as typical, accepted, and desirable, further encouraging their adoption.

Available options refer to the range of choices accessible to individuals within a given context. Social structures can influence behavior by introducing, modifying, or expanding these options to promote more sustainable alternatives. For instance, food retailers that promote affordable plant-based meals or tech companies that offer refurbished electronics help shift consumption patterns. By making low-impact choices more viable and appealing, organizations can enable sustainable behavior without relying solely on individual effort or motivation.

System: Infrastructures, incentives, and regulations

System refers to the broader economic, political, and regulatory environment that shapes behavior through three primary levers: infrastructures, economic incentives, and regulations.

Infrastructures are a foundational lever at the systemic level. By redesigning public spaces and systems, institutions can make sustainable behaviors easier, cheaper, more self-beneficial and more accessible while making unsustainable behaviors less convenient. Examples include expanding public transport, developing bike lanes, or building charging stations for electric vehicles, all of which shift the structural environment in favor of low-impact behaviors.

Economic incentives and disincentives influence decisions by altering the cost-benefit balance of different behaviors. Incentives can include price discounts, government subsidies, or tax exemptions. For instance, making public transport or electric vehicles more affordable, or reducing the upfront cost of solar panels. Disincentives, on the other hand, include taxes (such as carbon pricing), penalties, or the removal of subsidies for polluting activities. These measures help discourage high-impact behaviors by making them more costly or less attractive.

Regulations provide a direct means to restrict or shape behavior at scale. Governments and institutions can set legal boundaries through bans, restrictions, or mandatory standards. For example, low-emission zones can limit the use of polluting vehicles, while industrial regulations can impose efficiency or emission standards. Such regulatory tools are essential to reinforce long-term shifts and ensure that systemic changes are both broad and sustained.

Conclusion

The Snail Psychology is a framework to understand, design, and implement behavioral change by working across five interconnected layers. It begins at the center with the self, the internal and stable aspects of a person such as how they think, what they value, and the habits they form. From there, it moves into subjectivity, the shifting ways people perceive and feel about the world around them. Both self and subjectivity are shaped and reinforced by the social layer, where behaviors are influenced by what others do and expect. The spiral continues outward to structures, the way institutions shape choices through design, communication, and access. Finally, it reaches the system, the broader environment shaped by infrastructure, incentives, and regulation, which enables or constrains behavior at scale.

Importantly, the spiral is not linear. Change can start from any layer and influence the others. A shift in the system, such as new regulations or infrastructure, can reshape available choices (structures), redefine what is seen as normal or acceptable (social), shift how people feel or perceive their role (subjectivity), and even influence their identity and habits (self). This perspective reminds us that change is not only possible, it is scalable and interconnected.

The snail represents this systemic approach to behavioral change in several ways. Its spiral-shaped shell reflects the structure of the framework itself, where different levels of behavioral change are conceptualized as progressing from the self to the system. Beyond form, the snail also carries symbolic meaning. It evokes the necessity of slowing down, reminding that remaining within planetary boundaries requires decelerating our economies. Its delicate shell, which also serves as its home, symbolizes the planet as a home that must be protected.

As the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau once said, “Great moments create great people.” The climate crisis is one of those moments. Let us rise to meet it, together.

contact

I’m always happy to connect.

If you would like to apply the Snail Psychology in your organization, are working on a project, have data to explore, or just want to bounce around ideas, feel free to reach out: indaburu@bu.edu.